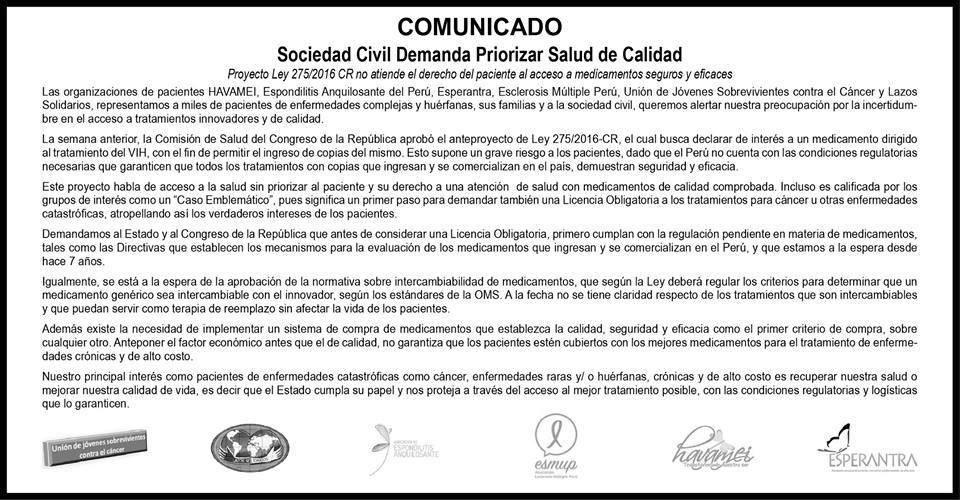

On the morning of 31 May 2017, Peru’s principal financial newspaper published a half-page advertisement which appeared to contain a serious warning. Entitled “Civil society demands prioritization of quality health”, it was a public statement opposing a bill which, according to the text, “would not address the right of patients to access safe and effective medicine”. A few days earlier, the congressional Health and Population Commission had taken the first step to declaring the antiretroviral drug atazanavir to be in the public interest, a move that would release its patent and facilitate the entry of equivalent and cheaper generic brands already available on the international market. Paradoxically, the advertisement denounced the measure, harshly criticized by the pharmaceutical industry in Peru, as “trampling on the best interests of patients”.

The statement coincided with the position of the manufacturers and was signed by six organizations claiming to be the voice of users: Esperantra, the Union of Young Cancer Survivors, the Association for the Emotional Support of Patients with Adverse Diagnosis, the Peruvian Association of Patients with Ankylosing Spondylitis, the Peruvian Association of Patients with Multiple Sclerosis, and Lazos Solidarios. None of these groups represent the population directly affected by the medication under discussion—HIV patients. In addition, with the exception of Esperanta, none is formally registered or has a website that identifies its representatives.

DIRECTOR. Industrial engineer Eva María Ruíz de Castilla gives a press conference on biosimilar medicines at Esperantra headquarters. /Esperantra

When Ojo-publico.com contacted Esperantra by telephone, its Executive Director Karla Ruiz de Castilla claimed she was aware of the other signatory associations to the advertisement and said she usually coordinated activities with each of them. She advised that she would represent all groups in the event of an interview with Ojo-publico.com. It turns out that Esperantra lacks transparency about its funding sources, its relationship with the pharmaceuticals industry, and the interests on whose behalf it has worked since its foundation in 2005.

Its most recent announcement uses the same arguments put forward by the National Association of Pharmaceutical Laboratories (Spanish acronym: ALAFARPE) to retain the monopoly held by one of members—the US manufacturer Bristol Myers Squibb—which exclusively sells atazanavir under the trade name Reyataz at a price 28 times higher than that paid in other countries in Latin America which allow the generic brand.

“Peru lacks the regulatory conditions necessary to ensure that all treatments entering and being marketed in the country are safe and effective”, claims Esperantra and its allies in the paid advertisement. They also add that this is “the first step to also demanding a compulsory license for medications for cancer or other catastrophic illnesses”.

PAID ANNOUNCEMENT. On 31 May 2017, Esperanta and five other groups used an advertisement to oppose the declaration of public interest in an antiretroviral drug.

This is not the first time that Esperantra has opposed the entry of generic medications into Peru. Curiously, its statements have always coincided with the position taken by the pharmaceuticals industry. Its advertisements published in 2014 and 2016 demonstrate this through their rejection of the use of biosimilar medicines—the name given for products that are equivalent to the costly biological and innovative medications used in the treatment of cancer, HIV, diabetes, and other chronic illnesses. In the case of atazanavir, Esperantra echoed ALAFARPE’s arguments: there are insufficient studies that guarantee its effectiveness and further regulation is necessary to ensure its quality.

This runs contrary to the position adopted in Europe and the United States—where regulations represent world benchmarks for the pharmaceuticals industry—which favors the use of biosimilar medicines. Since 2006, for example, the European Medicines Agency has authorized the use of 20 such products. At present there is no evidence of damage to the health of any patient that has used these drugs over the last decade.

Current Esperantra Executive Director Karla Ruíz de Castilla declined an interview to respond to this information, arguing that “the objective of the news item is unclear”. Her sister, Eva María Ruíz de Castilla—the previous occupant of the position, from 2007 to 2016—requested the questions be put to her by email, before finally responding from Miami, “I am on holidays this week. I will return to my activities in eight days and perhaps then I can recall (sic). Best wishes and good luck with the investigation”.

This was the way in which María Ruíz de Castilla avoided responding to Ojo-publico.com’s questions about the funding of her organization’s activities, its relationship with the pharmaceuticals industry, and the specific reasons why it opposes a public interest declaration in respect of an antiretroviral controlled by a pharmaceutical monopoly.

NETWORK. There are various HIV patients’ groups in Peru which favor breaking an Abbott monopoly and reducing the price of an antiretroviral. These associations receive no funding from the pharmaceuticals industry. /GIVAR

Like the majority of countries in Latin America, there are no regulations in Peru governing the financial relationship between pharmaceutical companies, patients’ groups, and doctors. The sector’s lack of transparency—which often contravenes the spirit of medical codes of practice—enables the pharmaceutical industry to pressure health systems through patronage of civil groups. “Nobody controls the pharmaceutical industry here and so it does what it likes”, warns Amelia Villar López, Dean of the Chemical and Pharmaceutical College of Peru.

Ojo-publico.com consulted the Ministry of Health about the situation, but its spokespeople had not responded to our questions by the close of this edition.

It is a global problem. In Spain, the Catalonian Association of Hepatitis Sufferers, which supports the “Sovaldi for all” campaign, received 400,000 euros from the US drug manufacturer (Gilead Sciences) that makes the medication. Sovaldi is known as the thousand dollar pill because of its high price. In the United States, the Restless Legs Syndrome Association was funded by the Glaxo and Boehringer Ingelheim companies, who market the drug used for the condition. Drummond Rennie, Professor of Medicine at the University of California—San Francisco, and associate editor of the journal of the United States Medical Association has written, “There are patients’ groups dangerously close to becoming extensions of the marketing departments of the pharmaceutical companies”.

The case of Esperantra in Peru brings together a number of concerning elements.

Pharmaceutical financiers

Eva María Ruíz de Castilla Yábar is an industrial engineer who studied international development at the Sorbonne in France. Her voice is soft and she has the appearance of a university lecturer. She assumed the position of Executive Director of Esperantra in 2007, and became the public face of the organization, which, according to the Public Records Office, had been founded two years earlier by Colombians José Gabriel Tafur and Martha Barreto. They were joint proprietors of Tafur Villegas and Cia Limited, a company which provided services to the pharmaceutical and petrochemicals industry and that had gone into liquidation.

Ruíz de Castilla began by advocating for social security to cover high-cost medications needed by a group of cancer patients. Her husband Maurice Mayrides had a role in the organization and various other family members occupied administrative positions. The organization’s agenda continued to focus on requests to the Ministry of Health for tightening of the rules about the entry of generic and biosimilar medications into the country. At no time did it take a critical position about medication prices, or the pharmaceutical monopolies that drive costs up. And it distanced itself from other groups who did so.

STRATEGIC PARTNERS. Pharmaceutical companies have special memberships with the International Alliance of Patients' Organizations according to the contributions they make to finance its projects. /IAPO

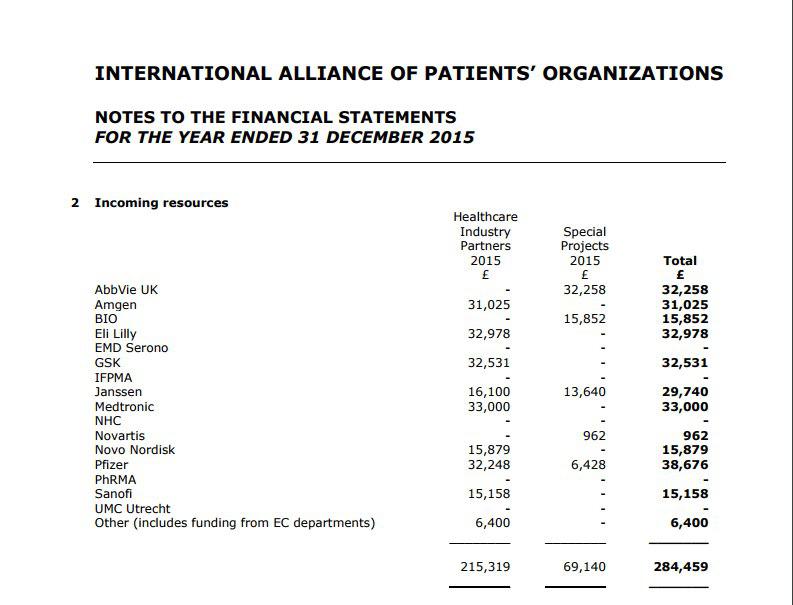

In parallel with her activities in Peru, Eva María Ruíz de Castilla was a member of the board of the International Alliance of Patients’ Organizations (IAPO) from 2009 to 2016. According to public information reviewed by Ojo-publico.com, IAPO is a network based in the United Kingdom which brings together 65 Latin American organizations—including Esperantra—whose sponsors include the 12 largest pharmaceutical companies in the world: AbbVie, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson (and its subsidiary Janssen), Eli Lilly, Medtronic, Merck Serono, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and Sanofi.

Ruíz de Castilla remained on the IAPO Board even whilst she occupied two public positions in the Ministry of Health. Between 2011 and 2012, she was National Director of Health Promotion—appointed by the then minister, Alberto Tejada—and subsequently worked in the Directorate for International Cooperation. Her husband, the Director of Policy and Programs for Esperantra until 2015, had previously worked for the Pharmaceutical Research & Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). This is an association representing drug companies in the promotion of public policies that support clinical research. Its members include AbbVie, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bayer Corporation, Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Glaxo, Johnson, Merck & Co and Sanofi. Mayrides now works for Alexion Pharmaceuticals—another PhRMA member.

Although Eva María Ruíz de Castilla rarely speaks in public about her relationship with the pharmaceutical companies, the international patients’ organization she helped expand in Latin America operates largely thanks to the money they provide. IAPO regional meetings in Mexico (2013), Rio de Janeiro (2014), Panama (2015), and Bogota (2016) were sponsored by 12 drug companies. The demand for tighter regulation of biosimilar medicines was a constant feature of these events, according to reports reviewed for this investigation.

MEETING. Migdalia Denis, the current IAPO representative for Latin America, at a meeting with patients’ organizations in Colombia. /IAPO

“We are completely independent, but the pharmaceutical industry is our strategic partner”, says the Venezuelan, Migdalia Denis, who suceeded Ruíz de Castilla in the position last September. IAPO has been registered in the Netherlands since 1999. Whilst it does not hide the identities of the sponsors of its events, it no longer publishes on its website financial statements or the amounts of the donations it receives. We asked Denis for this information, but she refused to reveal it: “I can’t tell you how much we collect, but we don’t have contribution limits. All projects are presented and the industry decides how much, if anything, to contribute, depending on whether and to what extend the projects are of interest”.

Ojo-publico.com accessed several IAPO financial reports and discovered that between 2011 and 2015 alone it received 3.38 million dollars from the pharmaceutical industry. The US firms Eli Lilly and Amgen figure among the largest contributors—$117,486 and 104,194 respectively. Each has a line of biotechnology products and has opposed the entry of biosimilar medicines into any market in which it operates.

An organization lacking transparency

Although Esperantra has never published the names of its sponsors, as a member of the IAPO it has used the organization’s logo for activities undertaken in Peru. In 2014 and 2015, IAPO supported some of Esperantra’s meetings, Cancer Week campaigns, and public discussions about the role of the patient in the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Esperantra also appears in public documents of the pharmaceutical company Pfizer, together with a series of organizations sponsored as part of the company’s corporate social responsibility program in 2010 and 2011.

The Peruvian Network of Patients and Users is another IAPO associate national organization. Its president Julio César Cruz states the following: “IAPO is divided into two groups: one which promotes access to medications of all kinds, including generics; and another, smaller group, that works on projects directly with pharmaceutical companies. We are in the first group. We receive no support from the industry”. According to this activist, while his organization has received funding proposals from Abbott, the code of ethics prevents it receiving money from drug companies.

FUNDS.This is the official 2015 report of the International Alliance of Patients' Organizations in which various big pharmaceutical companies feature.

Carmen Grasso, President of Oncovida Peru, makes the same point. This association was formed in 2005 to help cancer patients of the Guillermo Almenara Hospital with social security. Its policy is to operate without the support of pharmaceutical companies. Whilst it has been part of IAPO for three years, the president states that it has received no contribution whatsoever from the organization. “We joined to find out what type of advice they provided. But we have little contact with them. The only meeting we have attended was in Colombia and we paid our own travel costs”, states Grasso.

She assures us that the organization’s only funding sources are contributions from members, and the donations of family members and friends. “At times we have held sales events to help support our operations. But we don’t take money from companies. We are a serious association. That is why they have allowed us into hospitals. The problem is that many associations get created for personal reasons and then everyone is tarred with the same brush”, says Grasso.

Eva María Ruíz de Castilla now works as Latin America Regional Director for another civil society organization—the Global Alliance for Patient Access (GAFPA). This organization defines itself as a training network composed of doctors and defenders of the right of patients to access advanced medicine. According to its website, GAFPA’s vision is to “guide policy makers to make decisions about the value, safety, cost, and ultimately, patient access to advanced medicine”. It also identifies neither its sponsors, nor the names of its representatives.

Information gathered for this report shows that GAFPA is another organization that operates with funding from the pharmaceutical industry. The network is the international arm of the Alliance for Patient Access, a US NGO which in 2015 received more than 100 million dollars from the Abbvie company to produce educational materials aimed at doctors and patients.

MALPRACTICES. Use this tool to explore the history of fines and lawsuits against 13 of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies.

In March 2017, Matthew McCoy, a researcher from the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy of the University of Pennsylvania made public the findings of an extensive study which laid bare the need for pharmaceutical companies to be obliged by law to report the payments they make to patients’ organizations in the same way they do for contributions to doctors and hospitals in the United States. The research revealed that 86 out of 104 patients’ organizations in that country receive annual contributions from the pharmaceuticals industry that range in value between one and seven million dollars.

The links go beyond mere financial support: more than one-third (37) of the organizations researched had one or more board members who were also executives of pharmaceutical, biotechnology, or medical equipment companies.

“Greater transparency would enable citizens, researchers, and responsible politicians to assess conflicts of interests in organizations that defend patients in a way that is not currently possible”, wrote McCoy in an article published in the New England Journal of Medicine. His proposal for legislation that would order the reporting of industry payments to the organizations that defend patients interests could also be applied in Latin America, where the voices of a sector of patients have a decidedly pharmaceutical accent.