One evening in September 2016, Antonio, a Venezuelan Ministry of Health Employee, returned home without the anti-allergy medication his wife needed. After several long hours searching empty pharmacies in the state of San Francisco de Apure only one thing was certain: they both had to leave the country. The situation was complicated by the fact that they were both HIV sufferers. The stress caused by the permanent shortages of food and medicine was lowering their defenses. They urgently needed to restart their treatment. But in a Venezuela lacking not only antiretroviral reserves but even basic medications to treat flu or minor infection, the uncertainty was becoming as damaging as the illness itself. The couple did not yet know it, but the struggle to save their lives would take them on a journey through three Latin American countries to receive the essential drugs and medical attention needed to control the HIV virus. The final stop would be Peru.

Antonio and Pamela have been living in Lima with their little daughter for nine months. They moved into a rented room in the north of the capital of the only country where they could find employment to cover their basic living expenses. “We needed to restart our treatment, but above all we needed peace of mind. It has been very helpful in reducing our viral load”, says Antonio, a man of medium height and unhurried movements, who is seated at the premises of a civil society organization that monitors antiretroviral supply.

This family forms part of a wave of seven thousand Venezuelans who, through measures provided by the government, have been able to obtain temporary residence permits this year, according to information from the National Migration Superintendency (DIGEMIN). Although there are no official statistics about the specific number who have arrived for health reasons, since November 2016 the Antiretroviral Surveillance Group (GIVAR) has registered 20 Venezuelans who came specifically to restart their treatment regimes. “Messages continue to arrive from people asking us to help them obtain free medication here”, explains Marlon Castillo, coordinator of this group located in San Martín de Porres, a large district in Lima’s north.

DESPERATION. Thousands of patients protest in the streets about the lack of medicines in Venezuela. /StopVIH

In fact, Peru is not the first choice for Venezuelans migrating for health reasons. First they must reach the Ecuadorian cities of Quito and Guayaquil after an exhausting overland journey that begins at the Simon Bolívar International Bridge linking Venezuela with the Colombian city of San José de Cúcuta. The migrants initially opt for Ecuador because the procedures through which foreign citizens can access health services and free antiretroviral treatment are fast—certainly faster than in Peru. They need only present an identity card, their clinical history, and attend some briefing sessions. “The problem there was not access. We were unable to find work and we ran out of money”, recalls Pamela, a 36-year old woman with a cheerful voice and expressive hands. Back in Venezuela she was a teacher in a public school. Now she now works as a salesperson in a clothing store in the center of Lima. Antonio, who was also a public servant, has obtained work as an assistant in a shirt factory in Lima’s Gamarra clothing district.

Before entering Peru the couple received medical attention over several weeks at Guayaquil’s Infectious Diseases Hospital. They made the decision to cross the border when they heard about the migration provisions made available by President Pedro Pablo Kuczynski. Previously Venezuelans had to obtain a refugee permit; however, in January 2017 the government approved a temporary residency permit exclusively for citizens of that country. The document, which is valid for one year, enables them to study, to work, and to be attended at health centers even though they lack health insurance. “This is humanitarian assistance, because of the situation facing Venezuelans. It is a way of reciprocating the assistance they provided to Peruvians during the years of terrorism”, says a DIGEMIN spokesperson.

Since the end of 2016, the Integrated Health System (Spanish acronym: SIS) has registered 2,667 foreigner’s cards. The card enables holders to receive medical care as if they were insured. As few Venezuelans have the document currently, their situation is different. “The situation is being assessed to see how we can include them in the system through a small contribution”, says María Cecilia Lengua Hinojosa, the doctor in charge of SIS evaluation and risk management.

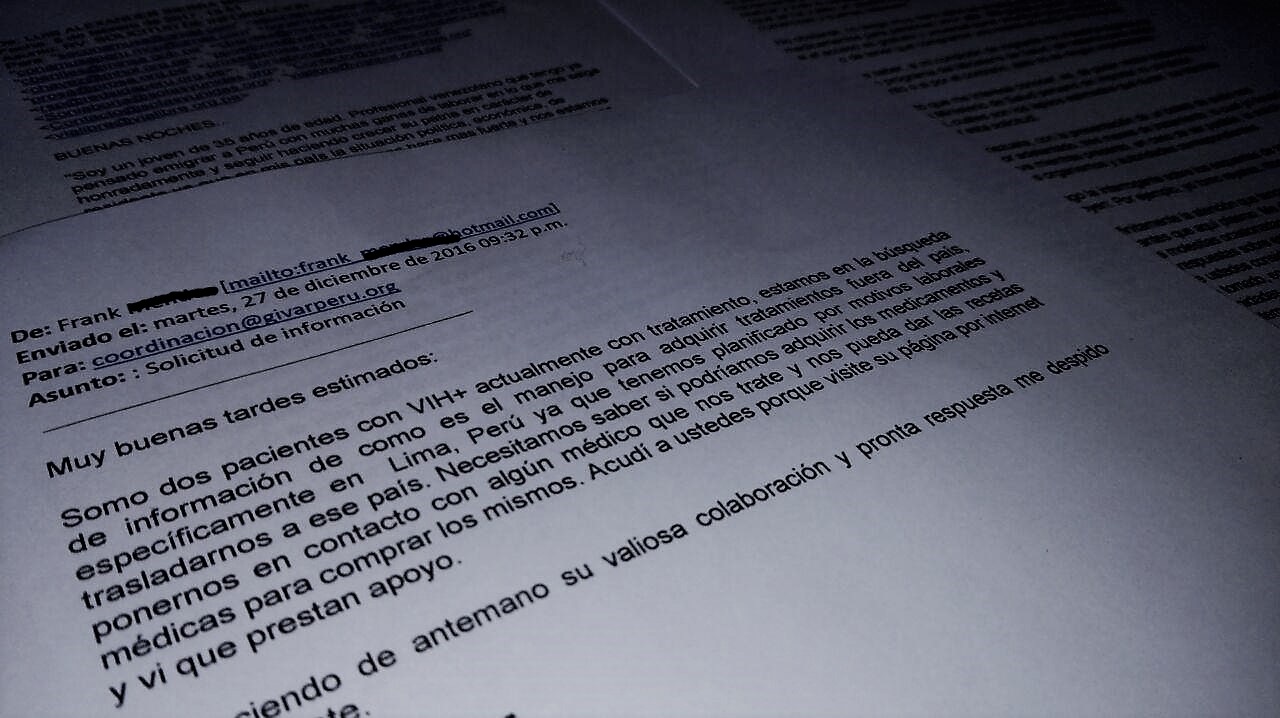

REQUESTS. Numerous Venezuelan HIV patients have made contact with GIVAR seeking advice about access to health services in Lima.

As antiretroviral treatment is universal and free around the world, foreign HIV patients receive their medication at no charge. However, those who lack medical insurance in Peru must pay a fee for the medical checkups. This is assessed at the social service centers in the hospitals.

This information appears in Facebook groups created to help other Venezuelan migrants follow the path to Peru. Pamela and Antonio convinced themselves that this was their opportunity. So they crossed the border by car at Huaquillas (Ecuador) and headed towards Zarumilla (Peru). They spent several days in Tumbes before finally catching an inter-provincial bus which took them to Lima. “Starting over again has not been easy, but we have been very lucky. We now receive care at the San Jose del Callao Hospital”, says Pamela.

An out-of-control pandemic

On the afternoon of 3 May 2017, Caracas was left without power. Jonathan Rodríguez, activist and president of the NGO StopHIV, had no alternative but to resort to the battery of his car to recharge his cel phone and continue our conversation using Whatsapp. Distressed, he wrote: “People die every day in Venezuela because of the shortage of medicines and hospital supplies”, before adding, “The government is totally indifferent”.

His organization has documented 66 instances of severe shortages of 25 antiretrovirals since 2009. This situation puts at risk the lives of more than 65,000 people living with HIV who depend on medication purchased by the Venezuelan state. In the absence of timely care, or because of difficulties that push them towards abandonment of treatment, many patients run the risk of becoming resistant to the medications and of their prognosis worsening.

According to Jesús Aguais, director of the US-based NGO Aid for AIDS, “What is happening in Venezuela runs contrary to all global efforts to control the pandemic. The lack of sustainable antiretroviral treatment in a country has serious consequences for its population: there will be more weakened patients, more new infection cases, and more deaths. But now, because of migration, there is the added risk of spreading resistant strains of the virus across borders. This will increase the threat from HIV worldwide”.

SHORTAGE. Venezuelan pharmacies have not received medicines for months.

In 2012 the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) warned that Venezuela was the country with the greatest antiretroviral supply problems in Latin America. The situation has become more acute over the last two years and is now affecting control of the illness. Figures available from UNAIDS reveal that deaths related to HIV/AIDS have increased. “In 1997 there were fewer than one thousand. By 2015 the number had reached 3,300”, indicates Michela Polesana, a communications officer for this regional UN organization. That is not the only problem: 44 thousand people in Venezuela are unaware they are infected with HIV, and an additional 5,600 new cases of infection are added every year.

Despite this bleak outlook, the Venezuelan Ministry of Health has failed to speed up actions that prevent the spread of the virus and the purchase of medicines for infected patients. In 2014 the government acknowledged that it only held 14 of the 30 medications on its procurement list. It could not even guarantee the supply of scar treatments and anticoagulants.

StopVIH has documented 66 instances of shortages of 25 antiretrovirals which have put at risk the lives of more than 65,000 people living with HIV.

The situation reached crisis point at the start of 2017 when some 90% of high-cost medications—primarily antiretrovirals and oncological drugs—failed to reach Venezuelan hospitals. Drug imports were curtailed because the state had insufficient funds to cover them. According to information about the pharmaceutical sector in Venezuela collected by The Big Pharma Project, the Ministry of Health has had a debt of 4 billion dollars to suppliers since 2014. At that time the president of the Venezuelan Pharmaceuticals Federations said the regime could recover the sector’s confidence by retiring 60% of the debt. But there is no indication that this has occurred.

Health authorities purchased antiretrovirals through the PAHO Strategic Fund in 2015 and 2016. However, Antonieta Caporales, one of three health ministers that Venezuela has had in the last six months, said that because of administrative problems this year’s purchases would not be made on time. “We were aware that each batch cost approximately 12 million dollars and that the government had no liquidity”, states Alberto Nieves, of the NGO, Civic Action Against AIDS, in an interview for this report.

The risk of resistance

When Elvis Ortuño left Valencia, the largest city in the Venezuelan state of Carabobo, he had to leave behind his family, his partner, and the final year of his education studies. It was March 2016. He had discovered that the antiretrovirals for the coming six months were not guaranteed and so he feared for his life. Barely a month had passed since he had received the news that he was infected with HIV. Viral load tests already showed his CD4 counts (a cell type that helps fight infection) to be below normal. “If I had stayed, I ran the risk of becoming resistant to the treatment and being unable to combat the virus”, explains this 35-year old, who now lives in Trujillo in the north of Peru.

Like many of his compatriots, Elvis Ortuño used the Internet to research alternatives that might be available overseas. He then began an overland journey towards Guayaquil, Ecuador. It was not an easy trip. He was warned to expect regular inspections by officials of the National Guard in the Caramuca region (in the state of Barinas) before being able to continue to his destination. “They made us get off the bus and checked our baggage. I saw them take two people away. They had supposedly found illegal merchandise. But there are constant reports that the guards themselves plant these things”, he relates.

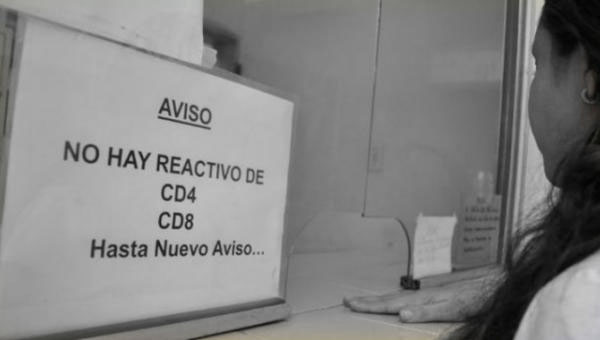

RESISTANCE. Because the reagents needed for testing are also unavailable, Venezuelan HIV patients do not know if the shortages, which have seen them without access to antiretrovirals for months, have left them resistant to their medication.

Ortuño’s problems began when he was stopped by officials at the San José de Cúcuta migration control point on the border with Colombia. The only way to continue his journey was to produce an airline ticket that would return him to his country, as proof that he did not intend to remain in Colombia. He spent one and a half days looking for ways to cross the border. He pleaded for hours with the police. He asked a doctor to provide him with a medical certificate. But nothing worked. He was only finally able to have his passport stamped and cross the border after showing an airline ticket reservation issued by an Ecuadorian travel agency which he had managed to contact.

“I knew that my life would change when I crossed the international bridge. It was like a sign of hope”, he recalls. Ortuño had just 120 dollars in his pocket, a small suitcase of clothes, and his final antiretroviral kit that would last for a further month. He would have to continue his journey from Colombia to Ecuador by bus.

After a 36-hour trip, this slim and tanned Venezuelan reached the Rumichaca International Bridge and was finally able to enter Ecuador. His destination was the Guayaquil Infectious Diseases Hospital and he had to take inter-provincial transport services to get there. Luckily, the hospital provided him with the medical attention he sought. He was able to obtain his medical checks for free, and the antiretrovirals were issued following a simple review of his clinical history. The next problem arose seven months later when he was unable to find employment to support himself. Returning to the Internet, he again began to look for somewhere else to go. This time he made email contact with GIVAR about receiving antiretroviral treatment in Peru.

In October 2016, Elvis Ortuño crossed a third border to save his life. He did not go to Lima. Instead he chose to stay in Trujillo, where he accessed a free antiretroviral treatment program at the Belén hospital and found employment as a waiter in a restaurant. He feels more relaxed now; his medical checks show that he has not become resistant to the medication despite interrupting his treatment several times.

“If many patients increase their viral load and become resistant to their treatment, the epidemic will get out of control”, explains Doctor Eduardo Sánchez Vergaray.

However, for the thousands of infected compatriots who remain in Venezuela, the anguish continues. “If an HIV patient stops taking their medication between the seventh and ninth month of treatment, their viral load increases and the drugs cease to have effect. If many patients increase their viral load, obviously the epidemic will get out of control”, explains Doctor Eduardo Sánchez Vergaray, President of the Peruvian Society of Infectious Diseases.

This year alone, there have been five episodes of antiretroviral scarcity in Venezuela. There has been no zidovudine for use with children since January. Since February there have been no reserves of Complera, a tablet containing rilpivirine, emtricitabine, and tenofovir. The situation is made more serious by the fact that due to a lack of materials to undertake testing, there is little chance of correctly measuring the levels of resistance in HIV patients. It has been three years since the last genotype test was performed on the Venezuelan population. And it is six months since there were reagents for the viral load analysis that each patient should undergo every three or four months. “We don’t know where we are”, states Elia Sánchez, infectious disease specialist and former president of the Epidemiology Society of Venezuela.

The Ministry of Health no longer prioritizes HIV even though it was one of the illnesses in which the Venezuelan state made the greatest investments following creation of a national program to control the epidemic in 1999. “The treatment regimes consist of old medicines. The country has no modern treatments because they are very costly”, says Sánchez.

Donations retained

In Venezuela the state has responsibility for importing medicines to supply pharmacies. Two non-government organizations have drug banks for donated medications: Caritas Venezeula, and the Coalition of Organizations for the Right to Health and Life (CODEVIDA)—through the Venezuelan Minority Action program, which provides donations sent by Venezuelans overseas. The shipments, however, are increasingly constrained and limited. ACCSI’s Alberto Nieves claims to have witnessed the way in which the authorities retain batches of medicines, which are then never distributed to the intended beneficiaries.

In 2016, Caritas International attempted to send 75,000 units of essential medications; however, the authorities confiscated the cargo at the airport. According to organization spokespeople contacted for this report, the government placed incomprehensible restrictions on the entry of these medicine batches.

Whilst the last reserves of Ministry of Health medicines are sufficient for HIV patients in Caracas, they are insufficient to supply states in the country’s interior, such as Valencia, Maracaibo and Barquisimeto, where cases have been reported of children and adults going four months without antiretroviral therapy. This is why increasing numbers of people, such as Antonio, Pamela, and Elvis, are deciding to make long journeys across Latin America to save their lives.

NEGATION. The government does not accept international support, despite the lack of antiretrovirals and reagents. /StopVih

Health authorities in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Panama have also reported that groups of Venezuelans with HIV have accessed their free antiretroviral therapy programs. Although no specific information is available about the number of migrants with the condition, the exodus of patients worries some Venezuelan NGOs, who fear that the time will come when the health systems in the other countries will see their budgets and medicine reserves affected and will begin to restrict coverage. In the Dominican Republic, for example, it is estimated that expenditure on foreign patients reached 1.48 million dollars in 2016. The majority were Haitian and Venezuelan. “The situation would be avoided if the Government were to recognize the serious public health problem we have and accept international humanitarian aid without conditions”, says Alberto Nieves.

The generalized shortage of medicines triggered a massive demonstration in May by patients and health professionals on the streets of Caracas. They resisted tear gas and a crackdown by National Guard, which tried unsuccessfully to prevent them from reaching the Ministry of Health.

The sick people taking to the streets had a single motto: “if we do not go out on the streets, we will die for lack of medicine".