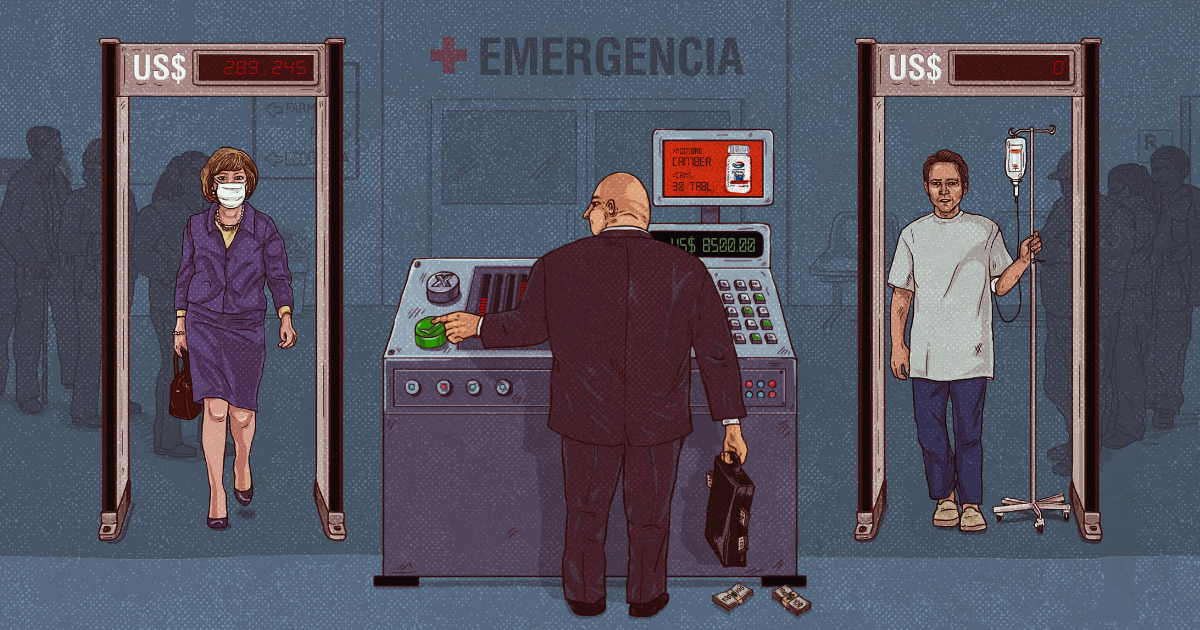

The penultimate meeting of the legal battle for access to high-cost medicines in Peru took place on Wednesday 10 May in a room at the National Congress: the Heath and Population Commission called a bill for debate that proposes to declare in the public interest the antiretroviral drug atazanvir—considered essential in HIV treatment. On one side of the table was a group of independent organizations and human rights defenders urging legal amendments that would reduce the cost of the medication; on the other side were representatives of the pharmaceutical industry and their allies from the country’s most powerful business guilds. The underlying issue was the continuation or termination of one of the most proportionally burdensome monopolies on the national health system.

The proposal being debated is an initiative of Congressman Hernando Cevallos, of the Frente Amplio (Broad Front) parliamentary grouping. It would represent a decisive step forward—following 27 months of discussion in various settings—towards the issue of a compulsory license for the medication. This is a legal measure that would remove the exclusive patent rights of the US drug manufacturer Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), permitting production and sale by competing laboratories.

DEMANDING. Civil society organization representatives promoting the compulsory license in a session of the Health and Population Commission that is studying the possible declaration of public interest in the drug atazanavir.

On the day of the session, BMS was represented by spokespersons of the National Association of Pharmaceutical Laboratories (Spanish acronym: ALAFARPE), the National Confederation of Private Business Associations (Spanish acronym: CONFIEP), and ComexPeru—the guild bringing together the country’s principal export companies. In the much anticipated exchange of arguments about the medication, CONFIEP spoke on behalf of the drug company:

“The proposal represents the possibility of indirect expropriation of a drug patent”, said Carlos Fernández-Dávila, lawyer and CONFIEP representative. “It is an attempt to bring health and property rights into conflict”, he insisted shortly after.

STOCKED OUT. In 2017 the state delayed the purchase of essential medicines to treat chronic illnesses. There have been continuous complaints about shortages since February.

This idea is the cornerstone of the private sector’s strategy to block the third attempt by the state and civil society to have the drug declared of public interest. It is not long since the same argument was used to neutralize a supreme decree project presented by the Ministry of Health (MINSA) with the same objective. The initiative provoked particular opposition from the ministries of economy and finance (MEF), foreign trade and tourism (MINCETUR), and justice. This is despite the fact that it aimed to correct the current monopoly position that forces the Peruvian government to buy the brand version of atazanavir for an amount 1,300% higher than the generic versions available in neighboring countries.

On this occasion, however, the result of the legal battle could be different.

The parliamentary initiative—that could eventually benefit more than one-hundred thousand patients—represents an alternative and more direct path towards obtaining the declaration. It relies on law rather than a supreme decree. It is backed by a favorable report of the Defensoría del Pueblo (Ombudsman) issued a day before the health commission session that crystallized the recent debate on the issue. According to the document—reviewed by Ojo-publico.com—the Defensoria states that “owing to the high HIV prevalence rates, the consequences of the illness not only in respect of health but also human rights […], and the high price of the medication under discussion, it should be declared of public interest”.

The parliamentary initiative represents a direct path towards obtaining the declaration by law, and is backed by a favorable report of the Defensoría del Pueblo.

This has been the clearest and most direct statement by a public institution in support of the declaration for atazanavir since MINSA’s neutralized project. In a letter sent to the president of the Health and Population Commission César Vásquez Sánchez (of the Alliance for Progress party), the Defensoría indicated that its position is based specifically on the impact medicine prices have on patient care and resource management: “An exaggerated or excessive cost, without reasonable justification, could mean a barrier of exclusion for other kinds of services”.

Alert setting

The proposal has been under debate in parallel with a crisis that passed almost unnoticed in the context of the national emergency generated by the El Niño phenomenon. On 15 March, while Peru was in the midst of a maelstrom of deluges and floods, MINSA’s hospitals began to run out of essential medicines to treat HIV. The steering committee of the Antiretroviral Surveillance Group (GIVAR), an organization that advocates for sufferers of the disease, reported a shortage of tenofovir 300 mg—a pharmaceutical also made by BMS. Takers of this drug become exposed to treatment resistance if its use is interrupted.

According to GIVAR, purchases had been delayed and MINSA facilities were restricting delivery of the tablets. “The situation is critical since the supplier won’t have the medicine available until the end of the month”, reported GIVAR two days later in a message on its social networks. By this time, all the state’s efforts and media attention was focused on the emergency in the north of the country.

"The problem is that there are constant shortages because of poor purchasing programming”, said Marlon Castillo, GIVAR coordinator, in an interview for this investigation The Big Pharma Project.

Despite the fact that medicine for numerous complaints should have been acquired in the final quarter of 2016, MINSA failed to achieve its stock objectives for the treatment of thousands of patients in 2017. As Ojo-publico.com reported at the end of January, various factors had also led to failure of the declaration of emergency which, through a supreme decree issued in September of the previous year to prevent shortages, had triggered the direct purchasing of medication without the need for tender.

DELAY. The Ministry of Health had the opportunity to ensure stocks during the health emergency declared in September 2016 that enabled procurement without tender.

Despite this, when the critical period of the recent El Niño phenomenon began and the government’s experts activated the mechanisms to shift from regular monitoring to alert levels, MINSA had still not purchased most of the 1.4 million tablets needed to treat patients with chronic diseases—not just people in national health system establishments, but also those in care facilities for the armed forces.

According to information published by the National Center for the Supply of Strategic Resources in Health (Spanish acronym: CENARES), the procurement of medicines in the first quarter of this year was well below what it should have been. During this period, proposals were submitted by the supplier laboratories for the antiretrovirals raltegravir (6 February 6), darunavir (7 February 7), etravirine (10 April), and atazanavir (17 April), in addition to the cancer drug trastuzumab (March 3).

Over this same period, GIVAR reported at least 28 incidents arising from a lack of antiretroviral products at hospitals in different parts of the country. Whilst these delays were not necessarily linked to the emergency, they aggravated it for patients who were at risk of dramatically compromising their situation because of interruption to their treatment. Ojo-Publico.com gathered the testimony of various patients about this recent shortage and about the difficulties of access they faced inspite of the law that guarantees coverage for the illness.

Delayed purchasing complicates the crisis caused by the high price of medicines. Four of the mentioned pharmaceutical products are on the list of the most expensive medications.

Raúl Raygada, a middle-aged industrial engineer, is a case in point. An HIV sufferer for two decades, he has participated in various committees as a patients’ representative. “You can’t stop taking the medication for even one day without the risk of a deterioration”, he commented in an interview for this special report. A problem accessing his medication years ago lowered his resistance and forced him to change treatment to a more sophisticated drug. So expensive was it, that an administrative process was necessary to gain access. Raygada cannot afford a similar episode; yet at the time of our conversation he had gone two weeks without his medication. “I had to fill out the complaints book”, he recalls.

The experience of María Luz Quispe—an HIV patient who now works as a counselor for new cases that reach the Carlos Lanfranco La Hoz Hospital in Puente Piedra—is just as sensitive. The 56-year old looks well even though she is an at-risk patient. She developed AIDS at one point, and has also suffered a bout of cancer which she was able to overcome. Her only alternative to treatment through the public system was using HIV medication sent from New York by an NGO. The product she has to use now is not included in the state’s annual medications requisition that determines the drugs to be used in the country’s health establishments.

“[These medicines] are purchased for very few people”, comments Quispe. [Only] for certain patients in certain hospitals. And I go to this hospital, because it is very expensive”.

At the time of our interview Quispe’s doctor had just sent a requisition for the US organization to subsidize the treatment.

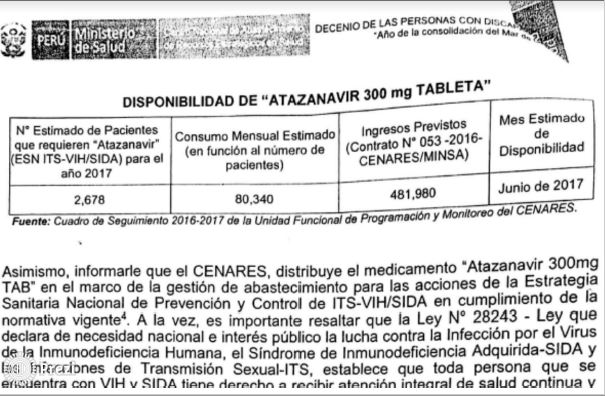

A review of the quantities requested by CENARES provides a sense of the impact of the procurement delays. The state requires 757,800 tablets of the atazananir antiretroviral—the majority for MINSA and some for the National Police Health Insurance Fund (SALUDPOL). It released a tender for the supply of 100,020 darunavir tablets for MINSA and another 39,000 for Essalud. Of the 100,720 etravirine tablets required, three-quarters are allocated for SALUDPOL and the remainder for MINSA. The same institutions have requested 414,900 tablets of raltegravir.

Some 5,380 doses of the injectable cancer drug traztuzumab are also required.

Delayed purchasing complicates the crisis caused by the high price of medicines. Four of the pharmaceutical products mentioned also appear on the list of the country’s most expensive medications.

The most alarming case is atazanavir: according to a CENARES report current reserves will not last beyond June.

WARNING. In October 2016, CENARES reported that atazanavir reserves were only assured until June 2017. Despite this, purchasing was delayed several months.

A hard pill to swallow

The demand for atanzanvir exceeds 80,000 pills per month for the 2,687 patients that are serviced in the state’s various establishments. It is imported by Bristol-Myers Squibb Perú S.A (a subsidiary of the US company), which exclusively sells the brand product in the country. “It is an essential medicine for which the state has paid up to 25 times more than the cost of a competing product”, points out Javier Llamoza, coordinator of International Health Action (IHA)—an independent organization that advocates against alleged abusive practices on the part of the pharmaceuticals industry.

This situation, which is often denounced by HIV patients’ organizations, has persisted despite official reports that have recommended specific measures to reduce the trade distortions generated by monopoly rights. A December 2014 EsSalud technical report pointed out the purchase of a generic version of the medication could have represented a saving of more than US$16 million over the last five years of the validity of the patent, which will expire in January 2019. Expenditure on this product represented 30% of the total allocated to the institution for antiretrovirals to 2012. The following year the figure was 53.2%

IMPACT. Use of atazanavir exceeds 80,000 pills per month for 2,678 patients. The state postponed until 17 April of this year the purchase of 757,800 pills.

The EsSalud report identifies the difference in cost of the medication in Peru compared to other countries in Latin America: whilst at present the Peruvian government purchases each atazanavir tablet from BMS for $10.50, in Brazil the same brand of tablet costs $2.60. And the gap widens when the cost per tablet of $0.50 for generic brands available on the international market is considered.

The critical situation led to meetings in 2014 between EsSalud and the drug company’s representatives to adjust the price of the product. This is an essential preliminary step before pursuing the compulsory license. “A minimal discount was achieved which maintained the price of the product well above that which the same manufacturer has set in other countries in the region”, the report states. Following negotiation, the cost dropped from PEN39.24 to PEN29.37

The EsSalud report proposed the declaration of atazanavir as in the public interest and attached a draft supreme decree.

According to the Peruvian Pharmaceutical Products Watchdog, part of the DIGEMID portfolio, the difference in prices compared to the rest of the region “is generating unnecessary costs to the health system”.

The General Directorate for Medications, Materials and Drugs (Spanish acronym: DIGEMID) drew a similar conclusion in December 2014. According to the Peruvian Pharmaceutical Products Watchdog, part of the DIGEMID portfolio, the difference in prices compared to the rest of the region “is generating unnecessary costs to the health system”. The report established that the use of generic versions of atazanavir would, by contrast, generate a saving of around US$35 million in the lead up to expiry of the patent. These funds could be used be to address other urgent needs in the sector.

After studying the available mechanisms for improving access to this medication, DIGEMID concluded, “the issue of a compulsory license would be the strategy to generate the greatest impact for lowering atazanavir prices in our country”.

The DIGEMID report backed the supreme decree proposal presented by MINSA to the Vice Ministerial Coordination Committee—the consultative body that precedes discussion in the Council of Ministers. It was there that the project faced its first opposition from various ministries: MEF, MINCETUR, and the Ministry of Justice. It was still held at that level when the change of government occurred.

The new administration returned the document to MINSA’s technical teams for a new assessment of its suitability.

DIGEMID sources confirmed to Ojo-publico.com that this specialist organization subsequently ratified its first report and added new elements that bolstered the argument for the declaration of public interest. Nevertheless, the proposal has still not been debated by the Council of Ministers and MINSA is currently forced to purchase atazanavir at PEN18.64 per tablet. Whilst this a lower price than before, it is still several times higher than the equivalent of PEN4.5 paid in Colombia and the PEN1.4 paid by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria—a global association joining governments, civil society, and the private sector to fund the struggle against these illnesses.

Drug companies versus civil society

The pharmaceutical industry has attempted to play down the public impact of atazanavir, as part of its strategy to present the compulsory license as a excessive measure that violates international agreements and laws about the protection of intellectual property. On the day of the session in the Health and Population Commission, the ALAFARPE spokesman argued that the international preconditions for approval of the proposal did not exist: an emergency situation, or serious limitations in patient access to treatment.

The industry claims that atazanavir represents barely 0.2% of the health sector budget, that only 20% of HIV patients use it, that there are three alternative treatments to its product, and that other measures exist such as parallel importation. The latter consists of buying the original medication in another country where it is cheaper.

“If you don’t like atazanavir, buy the substitute”, said Carlos Fernández-Dávila, the representative of CONFIEP and ALAFARPE.

“If you don’t like atazanavir, buy the substitute”, said Carlos Fernández-Dávila, the representative of CONFIEP and ALAFARPE.

The lawyer reinforced his arguments by invoking the position of the ministries opposed to the MINSA initiative. “MINCETUR ... has said there is no difficulty with access to the medication, and in consequence there is neither an emergency situation nor a public interest”, he stated. He also argued that MEF considers “the measure illegal and unjustified”, and that according to the Ministry of Justice “it does not pass the test of reasonableness” for indirect expropriation—a requirement demanded by the Constitutional Tribunal.

Ojo-Publico.com sought an interview with an ALAFARPE spokesperson but received no response.

The response came from civil society. In the same session, Javier Llamoza, of IHA clarified the compulsory license concept. “It has never been requested for emergency or national security [as claimed by the industry to deny the project’s suitability]. The public interest is the reason we are requesting the compulsory license”, he says.

DEFENSE. The industry argues that medication price is the only incentive for research. What they can’t explain is why medicines cost so much in countries where research is almost non-existent.

According to this expert, the text of the Free Trade Agreement with the United States—which opponents of the measure invoke as an insuperable barrier because the license would affect US companies—allows expropriation as a possibility (in this case, for intellectual property) precisely “because of the public interest”. Llamoza explained that the atazanavir case qualifies under this criterion because of the significant markup it represents for the state compared to the same product in neighboring countries, a difference the company has not been able to properly explain. Because of this situation, in the last four years Peru has spent PEN75 million unnecessarily.

“What is at stake here is the financial sustainability of the right to access health”, says Mario Ríos, of Justice in Health, a human rights organization focused on the difficulties facing patients in receiving medical care.

SPECIAL REPORT. The Big Pharma Project undertaken by Ojo-publico.com in an alliance with media organizations from six countries reveals the way in which multinational drug companies determine access to health in Latin America.

Civil society has international precedent on its side. This arises from a letter sent in May 2016 by the World Health Organization to the Colombian Minister of Health Alejandro Gaviria in relation to a similar case. “The unaffordable high prices of essential medicines, including for noncommunicable diseases, are a legitimate reason to issue a compulsory license”, indicates the missive from the highest global health body.

The fight is not over. ALAFARPE and CONFIEP have presented a prior matter to challenge the power of Congress to take steps towards the compulsory license. “Legislative decree 1075 establishes that the procedure is not a bill but a supreme decree to be debated in the Council of Ministers”, indicated the lawyer for the pharmaceutical companies to the commission. The industry’s objective is to take the debate back to the ministries that share its position.

The debate in Peru is taking place in the context of a regional controversy about the pharmaceutical industry’s tactics to prolong their manufacture and sale monopolies over the most expensive medications in Latin America, as an Ojo-publico.com report revealed yesterday in an alliance with media organizations from six countries. The strategies include diplomatic pressure, legal actions, conflict of interest relationships with public officials, and the systematic multiplication of patents that block the access of the most vulnerable populations to health services.

“Today it is HIV, but there are also problems with biogenerated anti-cancer medications and other rare illnesses which are not covered as part of a public health policy”, points out Julio César Cruz, Executive Director of the ONG Prosa which supports the process for obtaining the atazanavir compulsory license.

“This is market abuse”, said Javier Llamoza of the IHA, who views these maneuvers as symptoms of something more fundamental: “The commercialization of medication is becoming more cruel”.