The past 6th of December, when the shockwave of the Lavajato case hit the whole of Latin America, one of the last chapters of the war facing pharmaceutical companies against States and the patients went unnoticed at the hall of a luxurious hotel in Panama City. After two years of paperwork, representatives of a coalition of civil organizations secured a spot in a hearing of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to condemn a problem that puts the lives of millions of people at risk: the current patent system as the main obstacle to accessing drugs against severe diseases such as HIV/AIDS, Cancer and Hepatitis C. It was the first time that a group of speakers from Peru, Colombia, Argentina, Guatemala, Mexico and Brazil exposed before this forum that the rules of intellectual property allow for monopoly conditions for the big clinical laboratories to cause the prices of medications to soar.

“Multinational pharmaceutical companies have the control over a system that prevents the prescription of medications to all of those who need them”, says Germán Holguín, director of Misión Salud (“Mission Health”), the Colombian foundation that took the initiative of requesting the hearing. “More than 700 thousand people die every year in the region due to causes that could have been prevented”, specifies the lawyer and economist from Cali who has studied the behavior of the pharmaceutical industry for 15 years.

Holguín is convinced that all the conditions exist to label the behavior of the laboratories that block access to generic medications as a crime against humanity, which could be trialed by the International Criminal Court.

“We stand before a drama of gigantic proportions”, he warns.

SHORT DOCUMENTARY. The Big Pharma project tackles the war between pharmaceutical companies, the states, and the patients for access to high cost medications in Latin America.

Their worry concurs with the conclusions of the high-level panel on access to medications of the United Nations, who in their last report of 2016 identify it as a central issue: “the incoherencies between the rules of commerce and intellectual property with the objectives of public health and human rights”.

Within this context, Ojo-publico.com developed The Big Pharma Project, an investigation in alliance with journalists from Argentina, Colombia, Guatemala, Mexico and Venezuela, that reveals the pressure placed by the pharmaceutical companies upon States, in order to prolong their monopolies through diplomatic lobbying, court action, questionable links with government officials that represent a conflict of interest; the proliferation of patents through minor modifications to medications in order to extend their exclusive rights; and even lawsuits for collusion between pharmaceutical companies with the goal of blocking the sale of similar drugs at lower costs. The result offers an outlook of the questionable practices that explain the difficulty of access to costly medicines for vulnerable people across of Latin America.

Life or money

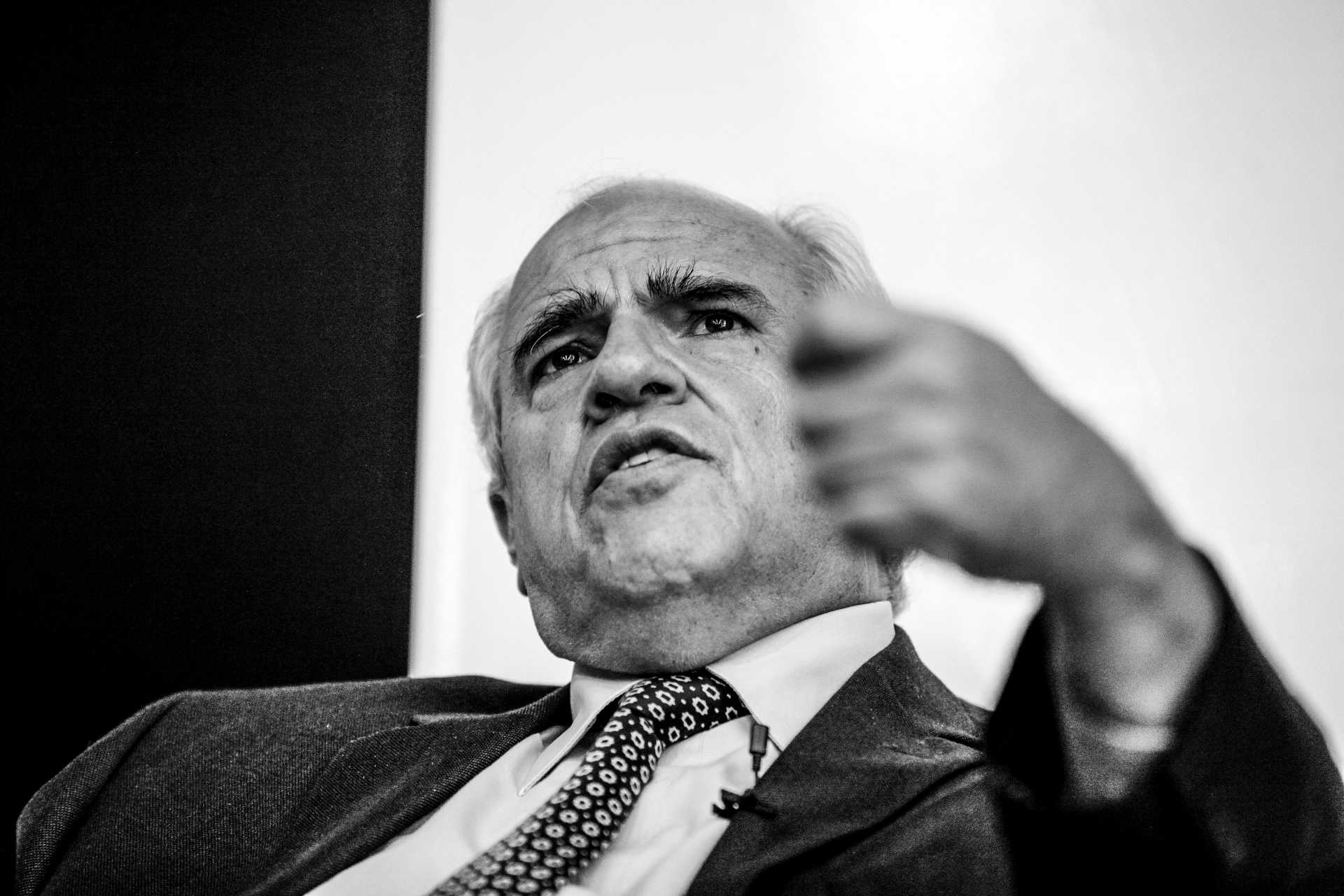

One of the most notable opponents of the big pharmaceutical companies’ behavior is the Colombian ex-president Ernesto Samper. In 1989, after suffering an attack that nearly cost him life, Samper required a blood transfusion that infected him with Hepatitis C. During a year and a half, he was subjected to conventional treatment as aggressive as chemotherapy, without any success. The cure arrived only later through sofosbuvir, a drug from American laboratory Gilead Sciences, which was launched into the market in 2014 under the brand Sovaldi, and for which his medical insurance paid 84 thousand dollars. This event made him discover, by experiencing it in his own flesh, the drama through which patients who require high-cost medications must go through.

“When one begins to look into how it is that a treatment can cost thousands of dollars per pill, when the cost of manufacturing is less than a thousand, you get answers such as: ‘That is how much a liver is worth’. As if it were: ‘Your life is worth 84 thousand dollars’”, tells the ex-president in an interview for this investigation. Until last January, Samper was Secretary General for the Union of South American Nations (USAN). There he discovered that the issue was much more complex.

EXCLUSION. A therapy against breast cancer with Avastin from Roche costs 36 thousand dollars in Latin America. There are women who die without having access to it. /Giancarlo Shibayama.

“When I was already cured, the same [representatives] from Gilead laboratories arrived to my office –at the Secretary of the USAN- to propose an agreement that would allow to cover the whole treatment for 6,400 dollars”, narrates Samper. “I said: ‘Perfect, but start transferring to me the 78 thousand that you stole from me’. Because, how can they lower the price for a treatment from 84 thousand to 6 thousand? They must be manufacturing it cheaper”, remembers the ex-president.

Prices so high as the one set for Sovaldi are instituted on the patent protection of 20 years, often justified by the presumed necessity to cover the costs of research and development. However, Gilead Sciences, the holder of the patents of sofosbuvir, did not invent this medication: it bought it. To be more precise, it acquired the company that had created it: Pharmasset, a small biotechnology firm based in New Jersey; and as if it were not enough, it is now known that the sale price of sofosbuvir exceeds, on average, more than 800 times its original manufacturing price: a study from the University of Liverpool concluded that the 12-week treatment with these pills can be manufactured by a price oscillating around 68 and 136 dollars.

The problem lays on the fact that few governments counterweight the abuses of pharmaceutical companies with compulsory licenses.

The problem lays on the fact that few governments counterweight the abuses of the pharmaceutical companies through a legal resource, which they have at their disposal in order to protect public health: compulsory licenses. These are authorizations granted to a laboratory in order to manufacture products that they could otherwise not manufacture due to their protection under patents. This mechanism is recognized within the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), valid since 1995, as well as the Doha Declaration, signed in 2001 by the member countries of the WTO.

SURVIVOR. The medical insurance of Colombian ex-president Ernesto Samper paid 84 thousand dollars for the therapy with Sovaldi that cured him from Hepatitis C. /Diego SantaCruz (El Tiempo)

A database on compulsory licenses, developed as part of the The Big Pharma Project investigation, reveals that between 1960 and 2016 only fourteen countries resorted to this mechanism, which led, in 44 cases, to the reduction of the prices of medications under monopolies from twelve pharmaceutical companies. These cases involved products from GlaxoSmithKline, Abbott, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Bristol Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences and Pfizer. The wide majority of the drugs released of their patents were antiretroviral medications, essential for keeping HIV patients alive, but there were also licenses for medications against cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, Hepatitis B, diabetes and other diseases.

Among the countries that figure in the list of countries that issued compulsory licenses, there are only two Latin American ones: Brazil and Ecuador. The former, which counts with a solid national pharmaceutical industry, made use of this resource in 2001 to cheapen the price of the antiretroviral Efavirenz, which was under a monopoly by Merck Sharp & Dohme; the latter, has granted ten compulsory licenses and has chosen to strengthen its pharmaceutical industry by founding the public company Enfarma, focused on the manufacturing of generic medications. In fact, in 2009, the same year in which Enfarma was created, the Government of Ecuador issued the executive order wherein access to medications used for the treatment of diseases that affect the population is declared of public interest.

Ecuador and Indonesia share the record of compulsory licenses in the world. The government of Rafael Correa released the patents of six antiretroviral medications that were in the hands of the laboratories Abbott and GlaxoSmithKline; two medications against arthritis, that were under a monopoly by Merck Sharp & Dohme and UCB Pharma; an oncological medication from Pfizer, and a drug used in kidney transplants manufactured by Syntex.

To the surprise of many, the list includes the US, who in 1960 was the first country to issue a compulsory license. Now it is opposed to their use in Latin America in order to protect the commercial interests of the American pharmaceutical companies. Compulsory licenses have also been granted by Italy (in 3 occasions), Eritrea, Ghana, India, Malaysia, Mozambique, Thailand, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

In five decades, only fourteen countries released, 44 times, the patents of medications in order to break pharmaceutical monopolies.

What has become clear is that in none of these cases were the apocalyptic warnings of the diplomatic representatives of the US and the multinational pharmaceutical companies fulfilled, about the imminent commercial or political sanctions for the counties that took this measure. Regardless of this evidence, the diplomatic and political lobby that moves this industry has just stopped these processes en Colombia and Peru, with the same arguments.

Colombia: the decree that protects the laboratories

At least for some time it was thought that the Health Ministry of Colombia had triumphed upon Novartis laboratories, when it achieved a price reduction of 18 thousand dollars to 10 thousand dollars for the therapy with imatinib to control chronic myeloid leukemia. However, president Juan Manuel Santos has just taken a turn that ratifies the power of the pharmaceutical industry. On the past 25th of April, Santos published the Decree 670, sponsored by the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, closing the door to making a new declaratory of public interest for medications that could lead to price controls or to processes of patent release.

The decree benefits multinational laboratories because it modifies the norm that regulates the process of approval for compulsory licenses and the new conformation of the technical committee in charge of evaluating them. Now, instead of being a team within the corresponding ministry, it will be an inter-institutional entity with the participation of representatives from the Ministry of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, and of the National Planning Office.

In 2016, the Colombian government desisted from driving a compulsory license for Glivec, as the drug imatinib from Novartis is known, after continuous pressure from officials from Switzerland and the US, who threatened with commercial sanctions and assured damages to the investments environment of the country. Because of this, the government only resorted to its price control system to cheapen a medication that was both declared of public interest and, on which around three thousand people around the country depend. However, the Association of Pharmaceutical Laboratories of Research and Development of Colombia now demands the repeal of such measure with the argument that it can hinder the country’s aspiration to access the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

April’s decree not only leaves the Health minister, Alejandro Gaviria, without support to continue with his actions to reduce the cost of medications in Colombia, but rather it represents a setback for the country’s posture against the strong international pressure promoted by the industry.

In the past two years, Gaviria had resisted the diplomatic attacks of the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs of the Swiss Confederation, Livia Leu, and of the president of the Swiss-Colombian Chamber of Commerce, René La Barré, who warned that Colombia would be entered into a “black list” of countries that do not respect intellectual property. The minister had also struggled with the threats of Everett Eissenstat, adviser for the American senator Orrin Hatch, who in April of 2016 gathered with diplomats of the Colombian Embassy in Washington and threatened with commercial retaliations to the country in case that a compulsory license were granted for the drug imatinib, as it was registered in an official notice of the diplomatic delegation.

Eissenstaat is chief adviser of International Commerce within the Financial Committee of the Senate, presided by the republican Hatch, who has had as well, for the past five years, the pharmaceutical industry as a major campaign contributor, according to the platform OpenSecrets.org .

Argentina: The ally of pharmaceutical companies

If the way is not diplomatic or political lobbying, the big medication manufacturers benefit from allies in key positions of a State who facilitate the protection of their interests. Since the arrival of the lawyer Dámaso Pardo to the presidency of the National Institute of Industrial Property of Argentina in 2016, the multinational pharmaceutical companies have a free path to obtain the prolongation of their patents and to restrict the access of low-cost generic medications into this country. Before assuming the charge, Pardo, a 58 year-old man with a good reputation within corporate circles, was a member of the firm Pagbam -Pérez Alati, Grondona, Benites, Arnsten & Martínez de Hoz, which advises multinational companies regarding intellectual property matters. Now, from his key position, he has taken care of approving an agreement that allows for greater flexibility regarding the granting of patents.

On the past 20th of January, Dámaso Pardo signed a memorandum of understanding with the United States Patent and Trademark Office that “tries to provide the procedure of resolution of proceedings with dynamism”. The agreement –examined for the investigation of The Big Pharma Project– establishes that the requirements for the approval of a patent could be considered fulfilled if the requesting party has obtained an equivalent certification from a foreign office, and without the need for the Argentinian authorities to perform their own examination of the request. “This is serious and we have requested Congress to inform about the reach of this memorandum”, says Lorena Digiano, lawyer and executive chief of the Fundación Grupo Efecto Positivo (Positive Effect Group Foundation), one of the civil organizations that were in the hearing of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Panama.

The memorandum of understanding leaves aside the current guidelines for the registration of medical patents that were approved during the government of Cristina Kirchner, guidelines that the multinational pharmaceutical companies consider as limiting, and for which they filled a lawsuit as a coalition, in order to override them. These guidelines intended to avoid abuses such as “evergreening”, a practice that consists of introducing minor changes in a medication’s formula in order to patent them again as a novelty and thus claiming for themselves the exclusive rights for their use.

The inclusion of the agreement with the US occurs just as the American pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences, manufacturer of the costly sofosbuvir for Hepatitis C, files paperwork in Argentina to obtain 39 patents for this pill: some for the manufacturing process, others for the family of components, and some others for its combination with other medications. If the patents were accepted, the sale of the generic medication would be blocked until the year 2028. The national industry and civil organizations are trying to stop this.

The inclusion of the agreement with the US occurs just when Gilead Sciences requests 39 patents for sofosbuvir in Argentina.

As long as Gilead Sciences lacks the patent for sofosbuvir in Argentina, the national laboratory Richmond will be able to manufacture its generic version, which is sold for 63 dollars per tablet in comparison to the 1000 dollars charged for the branded drug. Even so, the price turns out to be so expensive for the patients without access to the free medical insurance of the State, that some have chosen to bring the medication from abroad. “I was able to obtain the whole treatment for less than one thousand dollars from India”, narrates Pablo Víctor García, a patient, and now vice-president of Fundación Grupo Efecto Positivo. “I was cured, and without the side effects that other medications had”, he assures.

The interest of Gilead Science to maintain the monopoly over sofosbuvir is explained by the data that researchers from the Bloomberg Intelligence agency calculated: worldwide sales of medications for Hepatitis C could represent an income of over 100 billion dollars for the industry within a decade.

Mexico: the wall of prices

The pressure that the pharmaceutical companies’ power has over public health is demonstrated in different ways by controlling the available medications according to whatever is the most profitable for the laboratories. One proof lies on how the multinational company Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) delayed, for four years, the entry into Mexico of the potent antiretroviral drug Atripla, which the company manufactures since 2006, in order to not leave the State other options but to keep buying a cocktail of more expensive medications from them: the antiretroviral drugs efavirenz, emtricitabina and tenofovir. Atripla combines these three drugs in a single pill and costs a quarter of what the formulae cost separately.

Fernando, 17 years old, was born with HIV, and due to a head injury, he presents a slight speech impediment. /El Universal

On the same year that Merck Sharp & Dohme began manufacturing the drug, they announced that they would implement an agreement with Gilead Sciences to distribute it in Mexico at a cost of 1,032 dollars per year per patient. “When we found out that Atripla would make treatment easier, that our illness could be under control with fewer pills and our quality of life would improve, the majority wanted to have access [to this product]”, says a 42 year-old Mexican patient, interviewed in anonimity for this investigation. “But dut to its cost, it cannot be guaranteed for all of those who need it”, she adds. Indeed the price did not decrease, but rather it rose until it became one of the highest of the region. Currently, the cost of treatment with Atripla circles around 10,000 dollars per patient per year, according to the data analyzed for the investigation The Big Pharma Project.

Something similar occurs with Kaletra, a rescue medication for ill people who have a resistance to standard antiretroviral drugs, sold by the American laboratory Abbott. Even though in 2009 this pharmaceutical company reduced by 20% the cost of therapy with this drug in Mexico, its price remains to be much higher than in other Latin American countries. According to an analysis that we carried out for this report, Abbott sells the annual treatment with Kaletra for 2,161 dollars in Mexico, whereas in Peru it is worth 650 dollars and 214 dollars in Colombia.

Since a few years ago, a coalition of activists for the universal access to antiretroviral drugs, headed by the Aids Healthcare Foundation, demands MSD and other laboratories to reduce the costs of this medications in the country.

The underlying problem in Mexico lies on the fact that 80% of the supply of antiretroviral medications consists of patented drugs. Because of this, controlling HIV in a country with more than 140 thousand people with this diagnosis and 12 thousand new cases every year, costs the State increasingly more money. The crisis over access to medications could be worsened if legal resources block the production and manufacturing of low-cost generic products. The closer proof is in Guatemala, which also has serious issues for guaranteeing treatment with Kaletra to its patients.

Guatemala: barriers against generics

Various citizen collectives have asked the president of Guatemala, Jimmy Morales, to grant a compulsory license for the antiretroviral drug Kaletra, whose exclusive sale is in the hand of Abbott until 2026. Its position as market leader allows it to impose on the State a price of 803 dollars for the yearly treatment of a patient. But as the government keeps the request to release the patent on hold, big laboratories dominate the market for medications, supported by unbelievable barriers to the access of generic products in the third Central-American country with the most HIV cases after Honduras and Belize.

The best example is a resolution by the Constitutional Court of Guatemala –current since the end of 2015–, which forces importing companies to perform new studies on all the generic drugs that enter the country, as if their safety and efficacy were not already proven in the world. This resolution responds to a protective action presented by the J.I.Cohen corporation, main local distributor for the multinational laboratories Abbott, GlaxoSmithkline, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi Aventis and Merck Sharp & Dohme.

The argument of the distributor to request the action was the presumed protection of public health against bad quality medications.

CARE. A pharmacy worker from the Roosevelt Hospital of Guatemala checks the reserves of antiretroviral drugs. /Plaza Pública

J.I.Cohen’s legal action began around the same time at which The Global Fund for the Fight Against AIDS, TB and Malaria began its last phase of subsidies to the Guatemalan State for the purchase of antiretroviral drugs. In 2018, local authorities must take on the purchase of these medications with their own budget, and at that moment they will encounter a supply by monopolies with very high prices. This situation has set-off alarms within civil organizations such as the Human Rights and HIV Watch of Guatemala, since it could accentuate chapters of shortages and put at risk the therapies of almost 10 thousand patients who suffer from this condition in the country.

Just as in the case of Kaletra, another four antiretroviral drugs protected by patents (abacavir, lamiduvina, maraviroc and saquinavir) have higher prices in Guatemala than in other parts of the world.

Only between 2008 and March 2017, the State invested 23 million dollars on these medications. From this total, 7,1 million dollars were destined to six types of drugs with exclusive providers, which represented spending more than double the budget that would have been invested if generics had been bought instead.

After a series of consultations for this investigation, neither the Health Ministry, the Department of Patents and Registry of Intellectual property nor the Ministry of Economy responded clearly about which is the competent entity, and what are the procedures and the timelines to have a resolution for the request of a compulsory license for Kaletra. Actually, the expectations for the Executive Power to make use of this mechanism are low, since it has already given in to the pressure of the US before, for the patents of the big laboratories not to be affected. The diplomatic wires from the American State Department, leaked by the site WikiLeaks, prove it thus.

Some of these documents describe the lobbying by American ambassador John Hamilton with president Óscar Berger in 2005 for him to discard a law that promoted the entry of generic medications. The ambassador assured that this measure would jeopardize the free Trade Agreement signed by his country with Central America. Thus, Guatemala abandoned its intentions and included additional agreements that made the rules for the protection of intellectual property stricter in the country. “It has been the end of a drama that has unfolded for years (…). It has taken us longer than any other issue from the past few months”, told the diplomat in a wire about this case.

Twelve years after this chapter, the consequences are suffered by thousands of patients: hospitals with constant shortage of medications that the State delays to buy due to their high prices and lack of alternatives.

Peru: the battle arrives at Congress

It was believed that Peru had discarded the possibility of releasing the patent of an antiretroviral drug by Bristol Myers Squibb, which requires of 50% of its budget for medications against HIV/AIDS. But a bill from a congressman a few days ago, led the industry’s representatives, the Health Ministry and patient organizations to reopen the debate in Parliament. As we detail in a report, the discussion is now focused on the need for Congress to declare atazanavir, a drug of public interest, to pave to way for a compulsory license that prioritizes the health of the people over a pharmaceutical company’s business.

The annual cost of therapy with this medication in Peru is 3,832 dollars, more than is paid in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina and Chile. The difference is abysmal when compared to the special price available to the Strategic Fund of the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) for low income countries: 182 dollars per patient per year. If the State bought the generic version of atazanavir instead of Reyataz, the commercial brand of Bristol-Myers Squibb’s drug, it would save more than seven million dollars annually, as stated in a report by the Health Ministry revised for The Big Pharma Project.

COCKTAIL. Rescue antiretroviral medications are the alternative for patients who do not respond to conventional therapies, but their price is unmanageable for states. /Giancarlo Shibayama

The higher price is due to the fact that Bristol Meyers Squibb acquired a patent for atazanavir for its formulation as salts, which will only expire in January 2019, according to data gathered by the National Institute of Defense of Competition and of Intellectual Property Protection (Indecopi).

Between 2014 and 2016, the Health Ministry (Minsa) held negotiations with representatives of Bristol Meyers Squibb, seeking for a significant reduction of the prices, but little was spoken about what they offered the American pharmaceutical company in exchange. As he told the newspaper La República back then, the ex-minister of health Aníbal Vásquez, who took part in the meetings, the laboratory proposed that their product Reyataz were positioned in the first line of treatment. This is, that it was included in the initial scheme of therapy and not only as a drug reserved for patients who have a resistance against standard antiretroviral drugs.

This proposal would broaden the market line of Bristol Myers Squibb, but lacked any scientific grounds.

On the other hand, during the investigation for The Big Pharma Project, we found that between the years 2003 and 2004, the laboratory performed clinical trials in Peru on the efficacy of atazanavir in HIV patients without previous treatment, but never revealed the results. The reports of the performed clinical trials appear in the registry of the National Health Institute (INS), the entity that regulates medical experiments on people in the country.

As their therapy change proposal had no consensus, Bristol Myers Squibb obtained strong allies in their stance that a compulsory license would weaken the frame of intellectual property and could not be justified by the need to generate savings. In February 2015, the adviser minister of the US in Peru, Lawrence J. Gumbiner, met with minister Velásquez to discuss the topic and, soon after, the initiative of the Health Ministry to release the patent for atazanavir was overruled. By the end of the government of Ollanta Humala, the Economy and Finance Ministry declared the discussion as finished: the State would assume the extra cost of acquiring the medication under the current conditions.

A millionaire arrangement

This is not the only front in the battle to lower the costs of medications in Peru.

On the afternoon of last 12th of April, a month before he was relieved from his charge, the director of the Institute of Evaluation of Sanitary Technologies of Essalud, Víctor Dongo Zegarra, published a resolution that went by unnoticed until now, but that will save millions of dollars to the public healthcare hospitals of the country. The document ordered the removal of Lucentis, an injection against blindness, from the purchase list. It is a drug whose history is clouded by the interests of the Swiss laboratories Roche and Novartis. For this product, Essalud paid 1,5 million dollars annually in overprice since 2011, even though an equivalent drug that is cheaper and equally effective exists.

This case has as a precedent an investigation against Roche and Novartis that began three years ago by the judicial authorities in Italy. In this country both companies were trialed and fined after their mutual collusion was proved. They would stop doctors in public hospitals from disseminating and recommending a drug that is ten times cheaper than Lucentis, but that offers the same results.

The vial at issue is called bevacizumab, but is sold under the brand Avastin. It has manufactured by Roche for the treatment of various types of cancer over a decade. Although research by the American Academy of Ophthalmology, and by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Health Technology, demonstrate that this drug also has the property of controlling blindness, Roche has not registered this use before the regulatory agencies. Therefore, its prescription is not official and is done outside of norm. For ocular illnesses, the laboratory promotes the more profitable Lucentis.

In Peru, the public healthcare system was the main purchaser of Lucentis, which paid an overcharge of 9 million dollars for this drug during the last six years, according to an intern report and reports from the national system of public purchases. The main local provider was, precisely, their ally Novartis.

“The doctors would not prescribe the more economical medication, Avastin, because its use against loss of vision is not registered in a formal way”, said Víctor Dongo, interviewed for this investigation. Nevertheless, the panorama changed in 2015, when the World Health Organization (WHO) rejected the inclusion of Lucentis to its list of essential medications against blindness and incorporated Avastin for having the same properties and being cheaper. This was the basis that Essalud made use of, in order to withdraw it from its request form this year.

The business between Roche and Novartis with Lucentis began in 2006, when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the American regulatory agency, approved this sophisticated vial developed by the Genentech laboratory, owned by the former. That same year, Novartis secured the commercial rights over this product, with the exception of the US’ market, which was held by Roche. By then, both Swiss corporations were already aware about the effectiveness for ocular diseases of the oncological drug Avastin, but avoided to register this use. Lucentis became one of their star products, as proven by its current worldwide sales: Novartis perceives 2.38 billion and Roche 1.71 billion dollars annually from this medication.

The Scandal of the 1%

When Roche revolutionized breast cancer treatment with the drug trastuzamab, a vial sold under the brand Herceptin, the news were not a relief for all women who needed it. The therapy was fixed as such a high price that few healthcare systems in the world were able to cover it. Even today, twenty years after it was launched into the market, thousands of women in Latin America die without being able to access it. In Mexico, the annual 17-injections treatment costs 37 thousand dollars; in Peru it reaches the 36 thousand, whereas in Colombia it is set to 27 thousand dollars.

These prices generate an income of 6.7 billion dollars for the Swiss manufacturer. This is why Roche is seeking to maintain its monopoly through various means.

In India, the Swiss corporation has undertaken legal actions against the agency that regulates medications for allowing a similar, cheaper drug manufactured by American laboratory Mylan into the country. Meanwhile in Peru they acted as a coalition: the National Association of Pharmaceutical Laboratories (Alafarpe), of which Roche is a member avoided, with a precautionary measure, the entry of any similar drug that threatened the interests of the so-called biotechnological products of its members, among which Herceptin is present. The precautionary measure was valid since 2015, and was only recently lifted by the beginning of this year after reports of this case were published in Ojo-Publico.com.

WAITING. Patients waiting for care in the oncology wing of the hospital Puente de Piedra, north of Lima. /Giancarlo Shibayama

The prices for Herceptin vary from one country to another, but they all turn out to be unmanageable for any healthcare system, regardless of the fact that this therapy can be manufactured and sold at 240 dollars. Even at this price, it would generate a surplus of 50% for the pharmaceutical company, according to a study by the Institute of Clinical and Sanitary Effectiveness of Argentina, published in May 2015. The investigation, which covered access to treatment with the original trastuzumab in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Uruguay and Peru, warns that its price would need to be reduced by between 70% and 95% in order for it to be accessible to all the patients who need it.

The problem repeats itself with the majority of cancer fighting drugs, which every year represent a heavier burden on the states’ expenses.

In January 2017, during the last European Cancer Congress, the results of an analysis on the costs of manufacturing the oncological drugs included in the List of Essential Medicines of the WHO, were brought out to light. The data revealed that diverse treatments could be manufactured for 1% of the price that is charged for them. “For example, imatinib, used against chronic myeloid leukemia, can be produced for 54 dollars a month”, exposed doctor Melissa Barber, of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine. However, the Abbott laboratories sell this therapy at exorbitant prices in the region: 26 thousand dollars in Mexico, 10 thousand in Colombia, and 7 thousand dollars in Peru.

What must happen for a patent system that is excluding millions of people from access to healthcare to be reformed? The debate has been instituted in Latin America and has an echo with civil organizations and democrat senators in the US, whose healthcare system is also unable to sustain the prices imposed by the pharmaceutical monopolies. The cases that The Big Pharma Project investigation begins to publish as from today, expose that the logic of the big laboratories has derived from scientific research for profit, lawful to schemes of abuse of the norms of intellectual property, that include anticompetitive practices and even illegal pacts between companies. The CEO of Bayer, Marijn Dekkers, gave the clearest explanation of this process three years ago. During an industry forum in London, the executive pointed out: “We do not develop medicines for the Indians, but rather for western patients who can afford them”.